The Good Councillor's Guide 2024

It gives me great pleasure to introduce the 2024 version of the Good Councillors Guide. This revised edition is a welcome and much needed resource.

It is essential guidance primarily for new councillors but also for those thinking about becoming a local councillor. New councillors have a lot of information to take in when they join a council, and the guide can help them understand this.

If you are reading this guide as a new councillor, I congratulate you on joining the council and thank you for taking up a civic office that can make a real difference to the community that your council represents.

Once the excitement of being elected or co-opted has subsided you may begin to feel a little daunted by the responsibilities you have taken on and your part in the democratic framework of local government. I hope this guide will help you understand more about your role, the difference you can make and help ensure you are acting within your council’s powers and duties.

Cllr Keith Stevens, Chair of NALC.

ACRONYMS AND GLOSSARY

| ACV | Assets of Community Value |

| AGAR | Annual Governance and Accountability Return |

| ALCC | Association of Local Council Clerks |

| CALC | County Association of Local Councils |

| CIL | Community Infrastructure Levy |

| DPI | disclosable pecuniary interests |

| GDPR | General Data Protection Regulations |

| GPC | general power of competence |

| JPAG | Joint Panel on Accountability and Governance |

| NALC | National Association of Local Councils |

| RFO | responsible financial officer |

| SAAA | Smaller Authorities’ Audit Appointments Ltd |

| SLCC | The Society of Local Council Clerks |

| SPD | supplementary planning document |

| VCFS | voluntary, community and faith sector |

INTRODUCTION

This guide is an essential tool for all councillors, whether new, aspiring, or existing members of a local council. It will help with understanding how this unique sector of local democracy works and how they can best contribute to it. Training and learning are a crucial element of being a good councillor and this guide is just the start of the process. Where relevant, this guide will show where more resources can be accessed, namely from your local County Association of Local Councils (CALC), which can supply essential training and development opportunities.

Throughout this guide, all community-level civil councils are referred to as local councils because, regardless of their formal title (Town, Parish, Community, City, Neighbourhood or Village), they all have the same tier of authority and duties. In effect, Combe Hay Parish Council (population 147) has the same duties and authority as Northampton Town Council (population 137,000).

The duties of the local council as a corporate body are not onerous, but respect should be paid to their long history – going back to 1894 – while staying relevant to a fast-paced modern world. Well-informed councillors find the role can be extremely rewarding and that they can make a difference in their communities. Accepting the unique role of a councillor at this tier of local democracy (which is different to those at principal tiers of the democratic system) can be a challenge, but new councillors are not expected to know everything when they start.

This guide aims to outline the basics. It touches on the quite distinct roles and responsibilities of councillors and officers, and the complexity for councillors in having to act collectively as one corporate body (and not as individuals) in their dealings with employees, whilst respecting their highly professional and crucial role. All councillors are recommended to read the Good Councillor’s Guide to Employment (2023 edition).

Local councillors are not ‘volunteers’ in the common use of the word. Firstly, local councils are not part of the voluntary, community and faith sector (VCFS). Local councils are the first tier of government, closest to the community. Once the Declaration of Acceptance of Office form is signed (and this must take place for someone to become a councillor), that person takes up the position as a holder of public office in a local authority, albeit unpaid, with all the responsibility that comes with it.

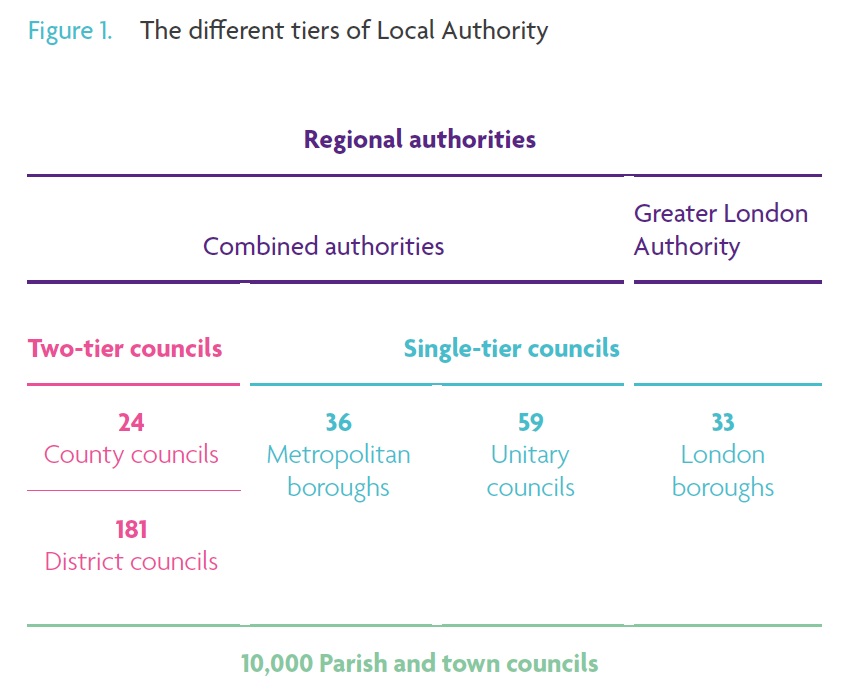

The other tiers of local authority are principal councils, including county councils, district, borough or city councils, and metropolitan and unitary councils, which have different statutory functions to local councils.

LOCAL COUNCILS AS LOCAL AUTHORITIES

Most local councils were set up in 1894 by an Act of Parliament. Civil parish councils (local councils) were created by separating them from the Church, which had had a long history of delivering local services such as care for the poor, maintenance of roads and tax collection.

Not all areas of England are covered by local councils, but there are now over 10,000 – and more are regularly being created all the time, especially in urban areas. In 2007, the government brought in new legislation to allow the creation of local councils in London (not allowed since the 1960s) and the first local council in London, Queen’s Park, began in 2014.

The number of electors a local council represents varies enormously. St. Devereux in Herefordshire has fewer than 100, whereas some have much larger populations. Northampton Town Council, created in 2020 and fully functioning by 2021, is the largest local council in England. Serving a population of over 130,000, it is larger than some principal authorities. These considerable differences are reflected in annual spending, which might range from under £1,000 to over £4 million.

The essence of a successful local council is one which has members that understand the clearly defined, and hugely different, roles of the councillors and the officers. They all need to work together as one dedicated team, utilising those separate roles and regardless of their personal political stance, to achieve a single purpose – to improve and enhance the lives and area of the community the local council represents.

A local council is a corporate body: a legal entity separate from its members. It is a collective decision-making body; its decisions are the responsibility of the whole of the council. All the councillors have equal rights and responsibilities, even the chair[1] or councillors who also sit on a principal authority are no more important than any other member. This means that councillors do not have any authority as individuals. In short, no councillor can act alone or speak on behalf of the council without first being formally granted the authority to do so by that council.

[1]: “Chairman” is the title given to the person who is elected by the council to preside at its meetings in law. It relates to both males and females, but most councils now refer to the positions as the chair, as a gender-neutral option.

It is also important to understand that local councils are autonomous and not answerable to a higher authority. They have been granted their own powers by Parliament, including the important authority to raise money through taxation (the precept) and a range of powers to spend public money (refer to ‘What local councils are obliged to do by law’ on p.29).

A question for councillorsDo you know how much your council spends in a year? If not, find out, as it is important that all councillors know. Ask the clerk/responsible financial officer for a copy of the most recently approved budget for your local council. |

THE PURPOSE OF LOCAL COUNCILS

It is clear from Figure 1 that each tier of local government has a different function. The duties and responsibilities of the members at each tier are also different, as is the legal framework in which they work. Duties are legal obligations – actions that a council must take by law. Powers are contained in legislation and allow actions to be taken at the council’s discretion.

Some councillors are members of various tiers of local authority at the same time and this can be useful to local councils, but it is important that those members know their differing responsibilities when acting at the individual tiers of authority and when it is appropriate to declare a conflict of interest due to this dual membership. If a member of another tier of local authority accepts a seat on a local council, they are equal to (not more important than) all the other members when performing as a member of that local council.

The various tiers of local authority can work very well together in partnership, but a local council cannot act on its own in delivering a service that is the statutory responsibility of another tier of local authority. For example, a local council cannot set up its own household waste collection service, as that is the statutory responsibility of a district or unitary authority. They can, however, in certain circumstances be delegated the powers of a higher authority, through a formal agreement to act on their behalf.

Regardless of their size and level of activity, all local councils must perform all their statutory duties set out in law. The legal framework is quite strict, but it is not too onerous. It is important for all councillors to understand that although this legal framework might be frustrating and sometimes slows down a local council’s ability to function, especially in this fast-paced modern world, acting in accordance with it is a legal requirement when dealing with public finances on behalf of your local community and being part of the democratic process.

In order to function and, especially, to supply more services to the community, the local council imposes its own tax on its residents. This is called the precept. The precept demand goes to the billing authority (the district, unitary or equivalent council) which collects this tax on behalf of the local council as part of its own council tax and pays it to the local council.

| Community safety, housing, street lighting, allotments, cemeteries, playing fields, community centres, litter, war memorials, seats and shelters, rights of way and some aspects of planning and highways – these are some of the things local councils might get involved with at this tier of government. Do you know which projects and initiatives your council is currently involved in running or developing? |

All local councils exist to represent the best interests of the residents of that parish, by contributing to the consultations of higher authorities and influencing the decisions they make, such as with planning applications. However, some local councils use the power bestowed upon them by law to act for the whole community’s benefit.

Local councils can, for example, supply or give financial support for:

- an evening bus taking people to the nearest town

- affordable housing to rent

- pond clearing

- redecorating the community centre

- a teenagers’ drop-in club

- a summer festival

- equipment for a children’s activity group

- transport to hospital

Projects like these may be a challenge and need hard work and commitment – but they are achievable for most local councils. Of course, for some very small local councils, with limited funds, it may be that representing their residents’ interests to the higher authorities (such as with planning applications and consultations) is the majority of their role, but good councils aspire to use the money they raise as a tax (precept) to provide services to improve the wellbeing of the whole community.

| Do you know how much your local council requests annually as its part of the council tax (the precept)?

Do you know how much a Band D council tax payer in your council area pays for the precept? How does this compare to the average? Is it low and could it potentially be raised to do more for the good of the community? Do you know when and how your council sets its precept? If not, please find out – it is important that councillors know, to inform their decision making. |

As a corporate body, a local council has a legal existence separate from that of its members. It can own land, enter into contracts and be subject to court proceedings. It is the local council that is responsible for its actions as a corporate body. Therefore, decisions can only be made in face-to-face meetings that have been properly summoned.

SERVING THE COMMUNITY

The best local councils want to improve the quality of life for people living in their area and enable them to become vibrant and flourishing communities. Local councils can be dynamic and professional in delivering services which can enhance the life experiences and wellbeing of local people. By devising clear strategic plans, such as action, corporate and business plans, which set out both the vision and the practical steps for delivering local services, the council can engage the community in the development of new services to help them come into effect.

There are powers set out in law that enable all local councils to provide services if they choose to utilise these powers (but they are not obliged to). Councils can undertake an activity only when specific legislation allows it. Acting without legal power is an unnecessary risk which could lead to financial and legal difficulties. The good news is that there are lots of sources of advice. The clerk will advise on whether the Council has the power to take decisions they are about to take. More information can be provided by your local county association.

In more recent years the general power of competence (GPC) was introduced. It is designed to make it easier for eligible councils to act and do anything that an individual might legally do if other legislation does not forbid it. The general power of competence enables local councils to respond more effectively to their communities, encouraging innovation and assisting in shared service delivery. If the council does something not permitted by legislation – even if it would be popular with the community – then the council could face a legal challenge that it acted beyond its powers (sometimes known as ultra vires).

| Do you know whether your council is eligible and has resolved to use the GPC? Achieving the eligibility to resolve to use the general power of competence might be possible for your council. GPC would facilitate the council being much more effective and innovative in providing services to the community. Ask your clerk about GPC. |

In recent years, the principal authorities have found it increasingly difficult to provide their non-statutory services. This gives the potential for local councils to work imaginatively in partnership with these bodies. Local councils can offer funding, equipment, and premises to help to provide these local services. They can also give small grants to organisations that run services such as childcare, services for the elderly, arts activities, pond clearance or sport which can improve the quality of community life.

To ensure that the local council is providing what is most valued by the community and what it needs in the way of improvements, it consults, engages and listens to as wide a range of all sectors of the community as possible to identify what is required; it then agrees priorities for action at its meetings, and its policies begin to take shape.

The tried-and-tested methods noted below are just some ways in which people can express their hopes and wishes for the community. They provide valuable opportunities for local people to identify features of the area that need improving or are worth protecting. They stimulate discussion, they inform the decision makers, and they usually lead to action.

- Surveys and questionnaires give residents, including children, an opportunity to express their views about where they live. The response rate from households can be impressive.

- Design statements involve communities in a review of the built and natural environment of their area. The published results can be used by your principal authority to help make planning decisions (for more, go to ‘Local development plans’ on p.72).

- A parish map can be a creative exercise; for example, it might be a painting, tapestry, or model of the parish. People identify local features that matter.

- Community conferences or workshops provide more opportunities for bringing people together to talk about the community’s future.

- Parish or Town (community) Plans might be led by the local council, drawing in community groups, residents, and others, to produce an action plan for improving the local quality of life and the environment. These plans can be based on the findings of a variety of the consultation methods above and can form the basis of neighbourhood plans (for more, go to ‘Local development plans’ on p.72).

- Technology provides options for creating polls and surveys online which can be highly effective at reaching a wider audience when used alongside traditional methods (for those who do not have online access). For example, SurveyMonkey™, Doodle™, the polling option from a Facebook™ page, etc. Informal meetings of focus groups on Zoom™ or Teams™ make conversations more accessible for some.

- Talking to residents whilst you are out and about in the community is of equal value in terms of keeping up to

date with resident views. This approach can easily be formalised by organising councillor surgeries where local residents know they can come and talk face-to-face with a councillor about issues and ideas they have.A parish (or town) plan is a community plan and not a land-use plan. It is a set of policies and an action plan for the next few years covering a much wider range of issues such as housing, the local economy, local health services and transport. It is a good idea to draw up a plan, whatever the size of your community. A local council that listens knows it will have local support for actions it may take.

With all community engagement it is important that the personal information of individuals is protected. The Data Protection Act 2018 came into force to protect such information. It is important that this law is respected when conducting any community consultation or engagement. For more information go to www.gov.uk/data-protection.

| There are occasions when the council will be required to meet certain levels of community engagement, such as with a Public Works Loan application, and the guidelines must be followed. However, community engagement generally is good practice. What community engagement has your council done? Was it compulsory or voluntary? |

Once the local council knows what local people want, they can decide how they are going to pay for it. Many councils start with the money and then decide how far it will stretch. Some councils claim they have so little money that they can do almost nothing. Evidence clearly suggests that local taxpayers would be willing to pay more if they could see the results in terms of better local services. It is recommended to ask first, and then set the budget accordingly.

Whatever the council’s approach to plan-making, if the council is raising a precept it is required (by law) to set a budget each year. The plan creates the budget that determines the precept. Remember, the precept is taken from the council tax. Your council should investigate other sources of funding such as grants and sponsorship to help implement its plans. In some councils, non-precept funding makes up one third of their income.

In addition to helping your council identify real improvements, the process of using tools like those above can strengthen people’s sense of purpose and belonging. The process is as important as the product or the result.

Councillors should, of course, use the knowledge they already have as a basis for decisions on behalf of your community, but these tools help you to become even better informed, giving the council a stronger mandate for action. The results of community consultation help you to:

- speak on behalf of the community with greater confidence, especially in discussions with principal authorities;

- provide services and facilities, especially where there is no other provider, or where the local council can secure better value for money;

- support community action and services provided by others. The council can offer buildings, staff expertise and funding to get local projects off the ground;

- work in partnership with community groups, voluntary organisations, and other local authorities, including neighbouring local councils, to benefit the community.

Occasionally there will be a conflict of interest requiring sensitive judgement. For example, dog owners, parents of young children and walkers might disagree about the use of the village green. Making challenging decisions in an open and reasoned way, along with appropriate use of social media (if used), is something that local councils need to do well.

COMMUNICATION AND SOCIAL MEDIA

A local council can make effective use of modern communications methods to communicate internally.

| Has the clerk advised you about what training is available for councillors? If not, please ask the clerk. You will learn a lot about your role reading this guide, but attending training sessions will give you more detailed information, the opportunity to meet other councillors and the opportunity to learn in more detail – particularly about complex areas like social media. |

Although decisions and formal discussions can only take place in a reasoned way at a correctly convened council meeting, there is nothing to stop councils having informal conversations and exchanging ideas in Teams™ or on Zoom™. The clerk (or an officer with delegation) should be party to such discussions.

Email discussions should be using a secure council email address, preferably with the .gov.uk domain. The council should take advice from an IT specialist.

Messaging apps are useful for informal communication too. However, it must be remembered that any such written communication between councillors is regarded as council data, which could potentially be requested under the Freedom of Information Act 2000 or the Data Protection Act 2018, and which must be provided if it exists. Councillors should act politely and respectfully in any communication, internally and externally.

In almost all cases a local council should have a website. Only the very smallest councils might rely on a website hosted by another organisation, and if they do, editorial rights for the clerk are essential. Nowadays, people expect to be able to go online to find out about their local council. If the council makes more information available on its website, it is likely to attract fewer public enquiries.

Councils with an income below £25,000 have a duty to publish certain financial information on their website; larger councils are advised to do so as a matter of course.2 Councils with an income above £200,000 have a separate code of transparency with additional responsibilities.

For local councils, acting as a corporate body, the use of social media to communicate with the local community and raise the profile of the local council is to be encouraged. If used properly it is a powerful tool and can successfully reach a more time-poor, younger or housebound audience. However, it is also important for the council not to rely on it completely; it should be used only in addition to more traditional methods of communication so as not to exclude residents without online access.

Communications about council activity should be managed by the officers using the council’s social media accounts. This is just the same as sending letters from the council “through the office”. The council’s formal social media accounts should not be used by councillors individually because they do not have any authority to act alone on behalf of the council. Posts should be controlled and monitored by an officer(s) to ensure they comply with the General Data Protection Act Regulation (GDPR) and the council’s own communications policies.

| What social media accounts does your council, as a corporate body, use as a method of communication

and engagement with the local community? |

It is advised that an officer (usually the clerk) be responsible for adding content to these corporate accounts. Please talk to the clerk for more information.

If an individual councillor chooses to use a personal social media account to communicate with the community, it is particularly important that they remember that the code of conduct and standards in public life rules still apply.

- They should not bring the council into disrepute and should act with honesty, integrity, etc.

- Councillors cannot rely on the fact that they are using a personal social media account to divorce themselves from the responsibility that they have under the council’s own Code of Conduct and civility and respect pledge.

- Once a decision has been resolved by the council, councillors should stand by that decision, as a member of that council.

- Councillors should not use social media to criticise the council’s decision, even if they voted against it. This is because a councillor’s own personal opinion is not paramount in the collective decision-making process of a local council.

- They should not give the impression that they represent the views of their council, as only the council officers can do that, on the corporate account and once a resolution has been passed by the council.

- They should not give the impression that they can act as individuals to resolve any issues raised by the public, as only the council can resolve to take any action.

If a councillor is using social media to campaign on an issue where a decision by the local council is yet to be made, it gets even trickier, because councillors must be careful to not give the impression that they will not keep an open mind for the council meeting at which that decision is to be taken. If not, the Council decision could be challenged based on predetermination. A good councillor attends a council meeting to listen to all arguments put forward before deciding which way to vote.

When communicating on a personal social media account about your council’s activity, if you are in any doubt about whether it would breach the Code of Conduct, leave it out. Do not risk a challenge and/or a complaint being made against you.

For further guidance on councillors using social media visit www.local.gov.uk/our-support/communications-and-community-engagement/social-media-guidance-councillors.

COMMUNITY RIGHTS

| Do you know about the community rights that came in under The Localism Act 2011? |

The Localism Act 2011 introduced new ways in which communities can act, collectively known as community rights. These include:

- The community has the right to bid on nominated buildings and land as an Assets of Community Value (ACV) if they come up for sale.

- The right to reclaim underused or disused publicly owned land to bring it back into beneficial use.

- Community Shares, a social finance model, help local groups (other than local councils) to raise money to do the things they want to do in their community through the issuing of shares which can only be issued by co-operative societies, community benefit societies and charitable community benefit societies. The Community Shares Unit, run by Co-operatives UK, provides support and information. Visit www.uk.coop/support-your-co-op/community-shares.

As local councils are closest to their communities, they can act – or assist other community organisations to act – in using these new initiatives for the benefit of their communities. Local councils up and down the country are already running a wide variety of public services successfully, from car parking to allotments and cemeteries, but in the past, it has been down to the district or county councilto decide whether and if to devolve services to local councils. More information can be found at https://mycommunity.org.uk.

WHAT LOCAL COUNCILS ARE OBLIGED TO DO BY LAW

THE RULES THAT APPLY TO THE COUNCIL AS A WHOLE

There are surprisingly very few duties, or activities, that a local council must carry out in law to deliver services to local people.

A local council must:

- comply with its obligations under:

- the Freedom of Information Act 2000

- the Data Protection Act 1998

- the Equality Act 2010

- publish certain information such as annual accounts, notice of meetings, agendas, and meeting notes

- comply with the relevant Local Government Transparency Code (further details in ‘Internal and external audits’)

- comply with employment law

- consider the impact of their decisions on reducing crime and disorder in their area

- consider the protection of biodiversity in carrying out their function

- consider the provision of allotments if there is demand from residents and it is reasonable to do so

- decide whether to adopt a churchyard when it is closed, if asked to do so by the Parochial Church Council – though it would be wise to seek advice from the County Association of Local Councils before doing so.

A local council also has a legal duty to ensure that all the rules for the administration of the council are followed. The council must:

- appoint a chair of the council to preside at meetings

- appoint officers as appropriate for carrying out its functions i.e. the proper officer (clerk)

- appoint a responsible financial officer (RFO) to manage the council’s financial affairs; although this is a separate role, the RFO is often also the clerk, especially in smaller councils

- appoint an independent and competent internal auditor (further details in ‘Internal and external audits’ on p.42)

- adopt a Code of Conduct

- hold a minimum of four meetings per year, one of which must be the Annual Meeting of the Council.

These rules are set out in law to guide the procedures of the council and your council can add its own regulations, formally agreed by your council, to its standing orders.

If the council does not have its own (non-financial) standing orders – although this is unwise – it is still bound by the duties set out for local councils in law, such as appointing a chair and a proper officer. NALC supplies model standing orders (and model financial regulations) which should be adapted, as appropriate, to the local council’s size and complexity, except items set out in bold type which are required by law.

All full council, committee and sub-committee meetings must be open to the public except in certain circumstances such as when dealing with:

- commercial tenders

- legal matters, e.g. seeking solicitor advice

- matters relating to individuals, e.g. staff matters.

These are not public meetings as such, but are local council meetings that must allow members of the public to attend, observe, record, and report the proceedings of the meeting.

Similarly, the law requires the council to have a publication scheme explaining how certain types of council information are made available.

Equality legislation reminds the council that it must make its meetings accessible to anyone who wishes to attend (at an accessible venue with disabled toilets, hearing loops etc. if possible).

THE LOCAL COUNCIL AS AN EMPLOYER

There are rules to which the council must adhere to protect its employees and the council as an employer. The most crucial points to note as a councillor are:

- Every individual councillor on the council is equal in their level of responsibility towards the employees, even if the council has delegated staffing matters to a staffing committee (which is strongly recommended). It is vital that all councillors understand that the proper officer (the clerk) is employed by the council and only answers to the council as a whole, a situation that is unique to the local council sector.

- All council employees, full-time or part-time, are protected by employment law in terms of pay, annual leave, sick leave, maternity and parental leave, bullying or harassment, and discrimination.

- All staff:

- must have a written particular of employment.

- must be paid (as a minimum) the minimum wage, or the national living wage for workers aged 25 and over.

- must have clear line-management arrangements, provided by a more senior officer who may report to the staffing committee. The only exception is the management of the clerk, who may be line-managed by the staffing committee (which can appoint one of its members to conduct regular appraisals (in consultation with all councillors)) but not directly line-managed by individual councillors.

Although all council members, including the clerk, are liable for the welfare of employees (regardless of whether they are on the staffing committee), no individual councillor can issue instructions to, or individually line-manage, the clerk as the clerk can only act on the approved stated policies of the council and on decisions of the whole council that are made at a correctly convened council meeting.

The clerk provides the council with:

- impartial professional advice

- administrative support

- project management skills

- personnel directorship

- public relations support

- information that enables a decision to be taken.

In smaller councils, the clerk might also take on the separate role of responsible financial officer, as this role must be performed by an employee that is accountable to the council (not a councillor).

The council might also employ other officers, with different employment arrangements, but it is the clerk who is the most senior officer. Councillors need to be mindful that all staff are protected by UK employment law and are entitled to be treated with dignity at work. It is the responsibility of all councillors to ensure that their staff are treated with respect – they may need to occasionally remind other councillors of this responsibility, to protect their own personal liability as a responsible employer. For further information it is recommended that you read The Good Councillor’s Guide to Employment produced by NALC (www.nalc.gov.uk/publications#the-good-councillor-s-guide-to-employment) and the Member Officer Protocol of the council.

It is the clerk’s responsibility to ensure that the council acts within the law and it is vital that all councillors take the advice of the clerk in terms of what the council can and cannot do. The main elements of this are set out in the previous chapter (‘What local councils are obliged to do by law’ on p.29), but the clerk is the first port of call for clarification and the fine details. Delegation is the act of authorising an officer, a committee, a sub-committee, or another council to make decisions on the council’s behalf. The delegations must be formally agreed by the full council at a meeting and set out in its standing orders (more later). Legally, councils can delegate most of their decisions to their clerks because they are trusted professional officers whose objectivity allows them to act for the council.

In the most successful councils, the individual roles of the clerk and councillors are clearly understood; i.e. the councillors stick to their own role and respect the professional role of the clerk. Failure to observe these primary principles can cause the council significant difficulties. The Local Government Act of 1972 does state that councillors can act as the clerk, as long as they are unpaid, but it is advisable that this only ever be a temporary arrangement – simply because it is an important part of a clerk’s role to be impartial and to advise and support the whole council, not allowing themselves to be unduly influenced by individual councillors, parties or factions. This crucial element of the clerk’s role is compromised where a councillor is also acting as the clerk.

These rules and principles should build on mutual respect and consideration between employee and employer. Misunderstandings can arise between a council and its employees, and so it is strongly advised that the council have an agreed grievance procedure to ensure that concerns raised by an employee are handled properly if they occur.

The Good Councillor’s Guide to Employment gives practical guidance on recruiting and managing employees effectively and in compliance with employment legislation. It is strongly recommended that all councillors (not just those on a staffing/HR committee) have read this guide and understand the implications for their role as a councillor. It is available on the NALC website and in hard copy.

EMPLOYMENT OF THE PROPER OFFICER (CLERK)

The proper officer is the official legal title of the clerk to the council. Councillors need to keep in mind that their status as a member of the council is for a maximum of four years, at which point they cease to be members until after the next election, when, of course, they may be re-elected to serve for another term of office. By contrast, the officers, and particularly the clerk, provide a consistent presence even if no councillors stand at the next election (or all the councillors resign or are disqualified mid-term); the clerk remains in post as the officiator, administrator, and practitioner of the business of the council. For this reason, it is particularly important that everyone – councillors and officers – regard themselves as equals but in very different roles. A councillor who claims to have served 40 years on the local council has in fact served ten separate terms of office.

The employment arrangements for the clerk are unique to the local council sector, in that the clerk is employed by the whole council and is only answerable to the whole council, not to individual council members. The clerk is not a secretary and is not at the disposal of the chair or any of the councillors.

The management and administration of the council’s business is the responsibility of the clerk and sometimes other employees, too. It is a very responsible role. All employees, including the clerk, are accountable to the council as a whole and therefore it is important that all councillors (though they cannot get practically involved) have a broad understanding of what that management and administration involves.

The budget is an essential tool for controlling the council’s finances. It proves that your council will have sufficient income to carry out its activities and policies in the coming year and creates the reserves it might need for any future initiatives the council aspires to undertake. By checking spending against budget plans regularly at council meetings, the council controls its finances during the year so that it can confidently progress towards what it wants to achieve. Transparency and openness are fundamental principles underpinning everything your local council does.

For further information see the Good Councillor’s Guide to Finance and Transparency (www.nalc.gov.uk/publications#the-good-councillor-s-guide-to-finance-and-transparency).

| Is your clerk also the responsible financial officer (RFO)? |

These guidelines clearly set out what should be made available to the public in relation to the council including reporting on meetings, public participation, and access to information.

In addition, the Transparency Code for Smaller Authorities (2015) applies to local councils and certain other small public bodies with an annual income not exceeding £25,000.

It replaces the need for external annual audit in most cases, but these smaller local councils are instead legally obliged, under the Code, to publish the following information:

- all items of expenditure above £100

- end-of-year accounts

- annual governance statement

- internal audit report

{{box|Have you read The Good Councillor’s Guide to Employment? Do you understand your responsibilities as an employer?]]

HEALTH AND SAFETY

Health and Safety law also protects employees, councillors, and members of the public when on council premises. Your clerk should be able to advise on such matters.

| Have you asked the Clerk about the Council’s responsibilities for Health and Safety? |

THE CIVILITY AND RESPECT PLEDGE

More information about building and maintaining positive relationships between officers and councillors is detailed in the NALC/SLCC (The Society of Local Council Clerks) Civility and Respect project, accessible at www.nalc.gov.uk/our-work/civility-and-respect-project.

| Has your council signed up to the civility and respect pledge? |

MANAGEMENT AND ADMINISTRATION OF THE BUSINESS OF THE COUNCIL

The officers manage and administer the council’s business, with the proper officer (clerk) taking ultimate overall responsibility for ensuring thorough and effective processes and staff management. The councillors are the decision makers and provide the strategic direction of the council’s work; they also play a scrutiny role, reading the reports provided by the officers and checking the details are correct. Understanding the internal control procedures necessary to carry out this task is vital.

DEALING WITH PUBLIC MONEY

The rules for dealing with local council finance are set by the Government and are designed to make sure that the council takes no unacceptable risks with public money.

Risk management must be a main priority of a local council (along with being a responsible employer), but the good news is that the financial regulations protect your council from potential disaster and your personal liability as a member of the council.

All money that comes into the council (even from sources other than the precept, such as development bonuses and grants) is considered to be public money, and must be administered within the council’s financial regulations and within the powers local councils have been granted by law.

Your council officers will set up a risk management scheme which highlights every known significant risk in terms of the council’s activities and makes clear how such risks will be managed. This must be formalised by the council as a working document. It includes ensuring that the council has proper insurance to protect employees, buildings, cash, and members of the public. For example, playgrounds and sports facilities must be subject to regular checks that are properly recorded. It is not just about protecting assets; it is about taking care of people.

The council shares collective responsibility for the fiscal management of public money; because of this, it must ensure that an officer known, in law, as the RFO reports all financial activity as transparently as possible on a regular basis to the council, to avoid the risk of loss, fraud or bad debt, whether through deliberate or careless actions. Robust financial checks and oversight are of immense importance.

Although it is technically a separate role, in smaller councils it is not unusual for the clerk to also undertake the RFO role.

A council can make electronic payments or choose to pay the bills by cheque; no matter the arrangement, there must be processes in place to reduce the risks of error or fraud. For example, the electronic payment should be set up, or the cheque made out, by an officer and then authorised by at least two councillors.

The broad principles of how a local council deals with public money are set out in its standing orders, but the finer detail, which protects the liability of individual councillors and ensures that the council gets value for money, is set out in the councils’ financial regulations. These rules can be frustrating and even counterintuitive for an inexperienced councillor. An example arises when goods needed are available on a website and could be bought by a councillor with a personal credit card, with the cost subsequently claimed back from the council. This is bad practice, because unless the order for goods is placed by the council (clerk or responsible financial officer), the council cannot claim back the VAT.

The National Association of Local Councils publishes model financial regulations, which are available from your county association. If the council has not adopted financial regulations, it is open to considerable risk and must correct this as a matter of urgency. An officer, namely the responsible financial officer, ensures that the council adopts effective internal control and financial accounting systems. The RFO must supply regular and easy-to-understand reports to the council, appropriate to your council’s expenditure and activity. There is extensive guidance on risk and internal control in Governance and accountability for smaller authorities in England – a practitioners’ guide to proper practices to be applied in the preparation of statutory annual accounts and governance statements, published by the Joint Panel on Accountability and Governance (JPAG).

| The term “officer” is used in this guide for anyone employed in any role to do with the management and administration of the council. This includes the proper officer (clerk), but also includes the responsible financial officer, deputy clerk, assistant clerk, project officer, administrator, etc. Where the information relates to a specific role, it is stated; i.e. clerk, RFO etc. |

The budget is an essential tool for controlling the council’s finances. It proves that your council will have sufficient income to carry out its activities and policies in the coming year and creates the reserves it might need for any future initiatives the council aspires to undertake. By checking spending against budget plans regularly at council meetings, the council controls its finances during the year so that it can confidently progress towards what it wants to achieve. Transparency and openness are fundamental principles underpinning everything your local council does.

For further information see the Good Councillor’s Guide to Finance and Transparency (www.nalc.gov.uk/publications#the-good-councillor-s-guide-to-finance-and-transparency).

| Is your clerk also the responsible financial officer (RFO)? |

These guidelines clearly set out what should be made available to the public in relation to the council including reporting on meetings, public participation, and access to information.

In addition, the Transparency Code for Smaller Authorities (2015) applies to local councils and certain other small public bodies with an annual income not exceeding £25,000.

It replaces the need for external annual audit in most cases, but these smaller local councils are instead legally obliged, under the Code, to publish the following information:

- all items of expenditure above £100

- end-of-year accounts

- annual governance statement

- internal audit report list of councillor or member responsibilities

- details of public land and building assets

- minutes, agendas, and meeting papers of formal meetings.

Although this Code only applies to local councils with an annual income of £25k or less, it is considered best practice for all local councils, whatever their turnover, to be meeting the transparency requirements it sets out. This best practice is reinforced by the NALC Award Scheme.

Local councils with an annual turnover exceeding £200,000 are expected to follow a separate Transparency Code specifically for larger authorities.

All local councils, whatever their size and income, must publish the year-end accounts on a website. Technically this could be a website belonging to another organisation with a local council page, but editing access for the clerk (who has responsibility for making sure the council abides by the law) is essential. NALC recommends that local councils have their own website and preferably a government (.gov.uk) domain name.

AUDITS

The clerk and/or RFO will arrange for the right audits to be carried out and can advise councillors on the correct order in which each stage of the process must be carried out, as this is specified by the external auditor assigned to the council.

INTERNAL AND EXTERNAL AUDITS

Internal audit is the first stage of the process and must be undertaken within the last fiscal year before the next stage, external audit, can be carried out. Larger councils with high turnovers or complex services to deliver may choose to have interim internal audits at various points throughout the year, for reassurance that all is well and that the council is functioning as it should.

The internal auditor is a competent person who is completely independent of the council; therefore, they cannot be a serving member of that council. They are someone formally appointed to carry out prescribed checks on the council’s entire system of internal control – not just the finances, which means they should not just be an accountant, as they need to have some knowledge of how a local council should lawfully run. A clerk for another council, especially if they are qualified, would be suitable, but it is important to note that a reciprocal arrangement between councils is not allowed.

The internal auditor must carry out tests focusing on all risk areas and report their findings to the council. They must then sign a report on the annual return, which is required by law for all councils (unless they make no financial transactions) to confirm that the council’s internal systems of control are in place and working effectively.

It is even more important for small local councils that the internal audit carried out is of a high quality and to a good specification, for public reassurance and to compensate for them being exempt from the external audit process (those with an annual income below £25,000).

The local county association can provide the council with model specifications of what is needed from an internal auditor, and example lists of what checks must be undertaken.

The Smaller Authorities’ Audit Appointments Ltd (SAAA) handle this stage in the process for local councils and appoint an external auditor every four years.

Councils with an annual turnover of £25,000 or less can send the external auditor a declaration that they are exempt from this part of the process (they cannot just ignore the process altogether). By doing so, that council is then obliged, under the Transparency Code for Smaller Authorities and the Local Government Transparency Code 2015, to publish a range of financial information on a website (www.gov.uk/government/publications/transparency-code-for-smaller-authorities).

If the council crosses this threshold of £25,000 at any point in the relevant fiscal year, such as by receiving a grant or contribution from a developer, they will be subject to the external audit for that year. Your clerk/RFO can supply more information. The law requires that all councils with an annual turnover over £25,000 must undergo this second stage of the audit process, called the external audit, so that local taxpayers can be assured that the risks to public money have been professionally managed.

The external auditors review the council’s annual return as signed by the internal auditor and the RFO and chair of the council in the prescribed order specified in their guidance (sometimes referred to as the AGAR – Annual Governance and Accountability Return). The annual return is the principal means by which the council is accountable to its electorate. Councils must complete an annual return to confirm that everything is in order. It includes signed statements confirming responsibility for the governance arrangements of the local council during the year. They show that: the accounts have been properly prepared and approved, a system of internal control is in place – this includes the appointment of a competent and independent internal auditor – and the effectiveness of both the system and the appointment has been reviewed

- the council has taken reasonable steps to follow the law

- the accounts have been publicised for general inspection so that electors’ rights can be exercised (www.nao.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/sites/29/2015/03/Council-accounts-a-guide-to-your-rights.pdf)

- the council has assessed all risks to public money

- there are not potentially damaging or hidden issues such as an impending claim against the council

- significant differences in the figures from the previous year have been explained

- the council has responsibly managed any trust funds.

There is also a specific requirement within the audit process which is to allow members of the public to inspect the council’s accounts and raise questions with the auditor. Officers handle all the practical tasks in carrying out the audit process, but it is the councillors’ responsibility to collectively, as a corporate body, ensure that the annual return accurately presents the fiscal management by the council. If councillors have acted properly leading up to the external audit, then the council will receive the external auditor’s certificate and an unqualified opinion on the annual return known as limited assurance. This means that nothing has come to the external auditor’s attention that gives cause for concern.

VALUE FOR MONEY

It is essential that the council is seen to supply value for money. This means ensuring that public money is spent efficiently to supply an effective service. The overriding aim is to achieve more council provision for the least possible expense, but without compromising quality.

It helps the council to assess ‘value for money’ if it regularly questions whether it is necessary to spend the full amount or whether another supplier can do the job with greater efficiency and effectiveness. Also, the council should engage with their service users and the wider community to find out what they think. It is sometimes possible to join with other councils to deliver a more economical service to the community.

The financial regulations and various statutes and procedures guide and protect a local council as it makes decisions in the proper manner. They also give the council the tools it needs to achieve its goals, protect community assets, and make best use of public money.

| If you have any questions about financial management, ask your clerk and/or RFO. Your local county association will provide training for councillors, which often includes training on financial management/responsibilities. |

THE ROLE OF A COUNCILLOR

There are over 70,000 local councillors serving in the 10,000+ local councils in England, all of whom will have met certain criteria to be eligible.

Ideally councillors on a local council will come from diverse backgrounds and have various enthusiasms and interests. Although not within the control of a healthy democracy (because selection is by election), a balance in terms of gender, age, ethnicity, educational attainment etc. is ideal, as a strong local council needs a range of skills and experiences.

When vacancies occur on a local council, usually from resignation, there is a notice period for the electors to decide whether they want a by-election. If ten electors do not come forward to request a by-election the principal authority will inform the local council that it is free to co-opt new councillors onto the council. If this happens, the existing councillors should aim to attract more councillors with contrasting personal attributes, different skills, and attitudes distinct from their own; this will ensure that the local council is a good reflection of the community it stands for and it should be celebrated if it can be achieved.

The role of a councillor is to work with all other members of that council to stand for the interests of the whole community as a balanced local council. Understanding the needs of diverse groups in your community (such as young and elderly people) is an important part of the role of a councillor.

The main task is to bring local issues to the council’s attention and help it make decisions for the benefit of the local community.

Councillors have a responsibility to be well informed, especially about diverse local views. You cannot assume that you stand for the interests of all your electors without consulting them.

If you stood for election, even if you were returned unopposed (meaning there were more seats on the council than the number of people wanting to be elected, so you automatically got a seat) you are classed as an elected councillor. If you were selected by the existing councillors mid-term of office (i.e. between elections) you are a co-opted councillor. Once you have formally accepted the office as a councillor it makes no difference – elected and co-opted councillors have the same voting rights and are equal when it comes to being selected for roles on committees, and even as the chair; all are councillors working together in the council to serve the community.

For many people, it is the satisfaction of acting on behalf of their local community that encourages them to become councillors. The next challenge is to make sure that the council acts properly and within the legal framework in achieving what it sets out to do. ‘What local councils are obliged to do by law’ on p.29 introduces the rules that guide your council – not as glamorous as action, but vital to its success.

| How does your Council consult with local people? |

DUE DILIGENCE

THE RULES THAT APPLY TO INDIVIDUAL COUNCILLORS

As a local councillor you certainly want to do something positive and, like most councillors, you hope to make a difference by influencing decisions that affect your community – but you must remember that you will be held accountable for your actions as a councillor by the local community you serve. The rules are there to protect your personal liability, just as much as they are there to assure the community that the council is working as it should.

The rules may not be exciting, but without understanding them your council could run into challenges and complaints.

- A council must do what the law requires it to do (‘What local councils are obliged to do by law’ on p.29).

- A council may do only what the law says it may do.

- A council cannot do anything unless it is allowed by legislation.

The crucial question is: does the council have the authority, set out in law, to do what it wants to do? This question is crucial if the council is to make a lawful decision to act, especially if it involves spending money.

| Check whether your council has the General Power of Competence (GPC). Beware of copying the activities of other councils without first checking, as they may be doing something under this power that your council is not entitled to do. |

Not Yet Fully Transcribed